https://note.com/akaihiguma/n/n1ab323be1b47

<転載開始>

Sam Parker 2024-02-05

https://behindthenews.co.za/bis-cbdcs-financial-collapse-war-part-1-of-a-4-part-series/

世界経済と金融システムの現状は、崩壊の危機に瀕している。このような状態になるのはずっと先のことだった。私たちの多くは、いつになるのだろうと思っていた。重要なシグナルは、2019年8月にウォール街で起きた8月の大レポ危機で、金融システムを救うために世界経済を封鎖することになった。その隠れ蓑として、コビッド詐欺が恐怖に怯え、誤った情報に踊らされた国民に放たれた。

なぜこのような事態に至ったのかをよりよく理解するためには、私たち市民が直面している危険を理解する上で、2つの要素が不可欠である。

ひとつは、1971年8月の金貨の非貨幣化である。ドルは無価値な紙幣となった。中東で戦争が起こり、人為的な石油不足で国民をパニックに陥れ、価格が上昇した。そして1年後、サウジアラビアを中心とするアラブの石油輸出国に、石油をドル建てでしか売らないように強要した。ドルは無価値な紙から、今では「ペトロダラー」と呼ばれる人気通貨となった。 ペトロドルの使用が強制されたことで、ドルは国際通貨となった。さらにアメリカでは、ドルを金融工学の道具とする規制法が成立した。その中で最も危険だったのは、金融システムへのデリバティブの導入だった。残念ながら、デリバティブの使用と乱用は、多くの企業や銀行に巨額の損失をもたらした。このような取引から生じた損失は、大西洋横断金融システムを崩壊させ、破綻させる結果となった。 この問題を少し整理してみよう。

第1部:-デリバティブの時限爆弾

2008年の金融大暴落は、金融デリバティブの乱用がもたらした暴落であった。

最初にリーマン・ブラザーズが破綻し、すぐにAIGがそれに続いた。しかし、このような失態がすべて公になるわけではない。誰もが知っているように、銀行取引はかなりの程度、信用取引である。預金者が預金は安全だと信じている限り、銀行は存続する。だから銀行家は、たとえ誤解を招くことになったとしても、大衆を安心させることが義務だと考えている。通常、銀行が直接問題を起こすまでは、一般大衆はそのことを知ることはない。

2008年に金融システムに亀裂が入らなかったからといって、もう少し大きな衝撃があれば、究極の金融の悪夢(銀行家がシステミック・リスクと呼ぶもの)が生じないとは限らない。それは「もし」ではなく「いつ」の問題なのだ。過去の金融危機は、数日あるいは数時間で金融システム全体が逆レバレッジによって崩壊する「大ショック」の前兆に過ぎない。

今日、私たちは史上最大の金融バブルに見舞われている。世界中のあらゆる金融機関が破綻しているか、それに近い状態にある。世界の金融取引高は1日約6兆ドルで、この金融システムに基づく債務がある。これらの債務のほとんどは目に見えないが、誰かが回収しようとすると目に見えるようになる。ギャンブルの借金のようなものだ。その時初めて、家族は何が起こっているのかに気づく。

ウォール街が崩壊しているからではなく、デリバティブ市場が崩壊しているからなのだ。銀行や投機筋は自分たちを守ろうとしている。

最短でも3営業日以内に、銀行が崩壊するだけでなく、金融システム全体が蒸発する。返済不能な債務が一度に発生し、それをカバーするための資産のマージンが事実上存在しないためだ。例えば、こうだ:あなたの財布を見てください。電子マネーはどれくらいありますか?実際の現金はいくらありますか?電子預金や電子引き出しとは対照的に、銀行から引き出したり、預けたりしているドルやユーロやポンドはどれくらいあるだろうか?あなたが頼りにしている信用供与のうち、現金とは対照的に電子信用供与の形をとっているものはどのくらいありますか?

その電子的信用とは何を意味するのか?それは、その電子信用をお金に換えることを保証する銀行機関があるということだ。では、その銀行が突然機能しなくなったらどうなるでしょうか?あなたはカードを持ってそこにいる。では、3、5日後に近所のスーパーマーケットで何が起こるでしょうか?彼らは電子マネーで機能している。食料品の在庫がなくなったらどうなるか。どうなるのか?食料品は手に入らない。サプライチェーンは崩壊する。制度が崩壊する。現代の経済では、人々は自分たちがいかに脆弱であるかを理解していない。私たちはもはや地元の農場を持たない。私たちは信用、特に電子信用と地元の商店に依存し、主に電子信用に基づいて一週間をやり過ごしている。その電子信用システムが崩壊したらどうなるか?世界中で大量の飢餓が発生することになる。商業システム全体が行き詰まるのだ。 何か対策を講じない限り、私たちが直面しているのはそのような事態なのだ。

システムの最も脆弱な部分は銀行間決済システムにあり(この詳細については別号で説明する)、それは市場の主要プレーヤーが被る損失の程度に左右される。

JPモルガン・チェース

例を挙げよう:JPモルガン・チェースの自己資本は1780億ドル、資産(ローン)は2兆1000億ドル。デリバティブは78兆7000億ドル!これは2010年12月31日時点のものだ。14年前だ。言い換えれば、自己資本はデリバティブ残高の0.24%に相当する。デリバティブポートフォリオのわずか0.25%に相当する損失が発生すれば、JPモルガン・チェースの自己資本はすべて消し飛ぶことになる!他の大手国際銀行の比率は若干良い。存在と崩壊の間にあるわずかなマージンが、今日の国際金融システムの支配的な特徴であり、これが金融業者、規制当局、政治家を恐怖に陥れている。一歩間違えれば、すべてが吹き飛んでしまう!すべてが吹き飛んでしまうのだ。デリバティブ市場の本質を理解するには、数学の世界を離れ、寄生虫の世界に入らなければならない。

犬は経済の生産部門を表し、ノミはウォール街の最悪の要素を表している。1970年代から1980年代にかけて、ノミは巨大な取引帝国を築き上げ、犬の血肉を売買した。ノミは大成功を収め、かつて強大だった犬は劇的に弱体化し、ノミが慣れ親しんだ方法で取引を続けるのに十分な血液を作らなくなった。賢い生き物であるノミたちは、みんなが喜ぶ解決策を思いついた。血液の先物取引を始めたのだ。実際の「商品」ではなく先物取引なので、もはや犬から吸える血の量に制限されることはなかった。取引は飛躍的に拡大し、ノミたちは想像を超える大金持ちになった。犬が死ぬ直前まで。要するに、これが今日のデリバティブ市場の本質であり、世界金融システム全体の本質なのだ。

新しいデリバティブの世界では、大手銀行は定期的に破綻している。

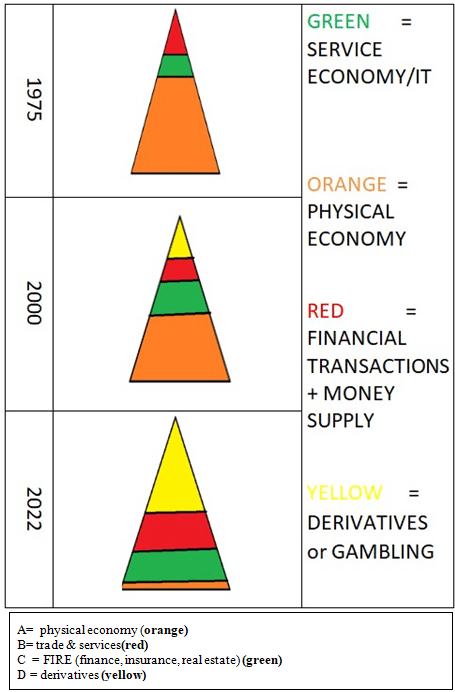

要約すると、世界経済における金融価値の巨大な塊は、逆ピラミッドの形をしている。ピラミッドの一番下には、実際の物質的財の生産がある。その上には、商品の商業取引と実際のサービスがある。その上には、負債、株式、為替取引、商品先物などの複雑な相互関連構造がある。そして最後に、デリバティブやその他の純粋に架空の資本がある。この奇妙な物体は、非常にアンバランスな形で成長している。デリバティブをはじめとする上層部は、下層部よりもはるかに速いスピードで成長している。しかし、ピラミッドの非常に薄い底辺では何が起こっているのだろうか。

実は、まったく成長していない。実際、1970年代以降、世界の実体経済は停滞し、衰退さえしている。 世界全体の状況を見ると、物理的生産高のうち農業、工業、インフラに還流する部分が減少していることがわかる。その一方で、架空資本は加速度的に増加している。

実際に起きているのは、世界経済の生産基盤がピラミッド型の金融バブルに「吸い殺され」ているということだ。これは、巨額の負債が蓄積され、農場や産業、さらには政府全体が機能停止に陥っていることからも、最もはっきりと見て取れる。金融バブル全体は、直接的にも間接的にも、世界経済の物質的基盤から増大する所得フローを搾り取ることに依存している。

これが、ニューヨークとロンドンによるグローバリゼーションと自由貿易の呼びかけの背景である。世界各国がこうした政策に賛同することは、自国の経済をこれら2つのネットワークに略奪される可能性を大きく残すことになる。ロンドンもニューヨークも金融バブルを必死に支えようとしており、そのためにさまざまな国の経済を「開放」し、略奪を容易にする必要があった。これらの国々が抵抗すると、指導者たちは「政治スキャンダル」によって不安定化させられ、さらに悪いことに、国家全体が不安定化の標的にされる。アメリカは破産寸前だ。すでに略奪された世界の他の国々から貢ぎ物を取り立てるために、政治的、財政的、軍事的な力を専制的に行使することによってのみ生き延びている。世界はアメリカを存続させるために、1日あたりおよそ30億ドルをアメリカに注ぎ込んできた。今、彼らは非常に疲れている。

現在の経済・金融危機は、起こるかもしれないものではない。すでに進行中のことなのだ。現段階でわからないのは、すでに存在する絶望的なシステムの破綻が、いつ街頭で爆発するかということである。それは、ひとつの出来事として起こるのか、それとも連鎖的に世界中を駆け巡る危機の累積効果として起こるのか、ということである。

これら2つのネットワークは、自分たちの経済・金融・政治システムが脅かされると、暴力で対抗する。言い換えれば、金融・経済システムによって世界をコントロールできなくなったとき、彼らはFISTという必死の行動で、自分たちの邪魔をする可能性のあるあらゆる人物を破壊し、粉砕するのである。

私たちは今、そのような時期にいる。現代史上最悪の金融・通貨危機である。 金融エリートが株式市場から救済される一方で、私たちのような愚か者は、同じ市場でさらに株を買うよう説得されている。最大手の銀行グループはすべて技術的に破綻している。ヨーロッパの状況はさらに悪い。推定40兆ユーロの融資残高のうち、ほぼ25%、10兆ユーロ相当が「不良債権」である。これらの融資は欧州の銀行に返済できない。EUの銀行カルテルの中心にいるのは、ロスチャイルドに支配された銀行である。これらの銀行は例外なく破たんしている。

日を追うごとに、英米帝国の金融業者からの緊縮財政要求は大きくなっている。世界中の政府が、予算を削減し、サービスを縮小し、社会的セーフティネットを細断し、国民を狼の餌食にしなければならないと言われている。「利用可能な資源はすべて我々に回さなければならない。「われわれには金が必要なのだ。同時に、このような非人間的な要求をしている金融業者ネットワークは、様々な公然・非公然の救済策、通貨操作、デリバティブ詐欺を通じて、地球から略奪を続けている。

インターアルファ・グループ

先に説明したように、今日の世界には2つの金融ネットワークがある。ひとつはニューヨークを拠点とするロックフェラー一族。もうひとつはロンドンを拠点とするロスチャイルド家である。この陰謀の中心となる重要な金融グループのひとつが、イギリスの男爵で金融家のジェイコブ・ロスチャイルド卿が支配する金融シンジケート、インター・アルファ・グループである。私たちは岩を持ち上げ、この寄生虫集団に陽の光を当てよう。公共サービスとして、またこの害虫が地下室の暗闇に逃げ帰るのを見る楽しみとして。しかし、彼らを特定することは始まりに過ぎない。人類が生き残るためには、インターアルファ・グループを破壊しなければならない。

インターアルファ・グループは1971年、ヨーロッパの銀行6行によるシンジケートとして設立された。

インターアルファ・グループ、2010年

ロイヤル・バンク・オブ・スコットランド(英国

サンタンデール銀行(スペイン

ソシエテ・ジェネラル(フランス

インテサ・サンパオロ(イタリア

ING(オランダ

コメルツ銀行(ドイツ

AIB(アイルランド

KBCグループ(ベルギー

ノルデア銀行(スウェーデン

ギリシャ国立銀行(ギリシャ

ポルトガル、エスピリト・サント銀行

大英帝国の栄光のために国民国家とその民衆を破壊するための道具としての本質は少しも変わっていない。ロスチャイルド一族は1800年代から世界の金融界を牛耳っており、フランクフルトを拠点に、ロンドン、パリ、ウィーン、ナポリにも銀行を設立した。同ファミリーはベネチアン・イルミナティ方式で運営されており、特定の国家に縛られることなく、帝国寡頭政治を敷いている。帝国寡頭政治は、自らを単なる国家のレベルより上位に位置づけ、国家を実質的な主権を持たない植民地とみなしている。この帝国は、国家を互いに敵対させ、負債に深く引きずり込み、いわゆる「独立した」中央銀行という仕組みを通じて通貨発行を支配することによって存在している。ロート製薬一族は初期の頃、ベネチア諜報機関の有力者トゥルン・ウント・タクシーズ一族を含む、ドイツのイルミナティ工作員ネットワークに拾われた。これがロスチャイルド家の悪名高い諜報・伝書ネットワークの源であり、内部情報を利用した取引を可能にし、彼らを大金持ちにし、ライバルを打ち負かす力を与えた。ロスチャイルド家の背後には、イルミナティのネットワークがある。

それは彼らの歴史だけでなく、現在の活動を理解する上でも極めて重要である。ロスチャイルド家は、このアングロ・イルミナティ帝国のためのダーティ・マネー活動を専門としており、インターアルファ・グループはその役割を反映している。グループ内の銀行は、ヨーロッパで最も権力を持つ一族のファミリーファンド(またはフォンディ)を代表し、その資金を一般大衆の目に触れないように展開する仕組みを提供している。これらの旧家はヨーロッパ中の飛び地にあり、巨大な権力を行使しているが、その権力と影響力を一般大衆から隠蔽するため、目立たないようにしている。ある種の昆虫のように、彼らの生存には暗闇が不可欠なのだ。

これらの銀行はすべて「プライベート・バンカー」として、帝国エリートのフォンディを専門に管理している。

インターアルファ・グループは、これらオリガルヒ一族とその富と権力のパイプ役である。インターアルファ・グループは、人類を農民として維持し、必要に応じて略奪し、役に立たなくなったら放り出すことで存在する略奪システムを象徴している。これが敵の顔なのだ。インターアルファ・グループが象徴する中世のプライベート・バンキング・システムは、比較的少数のオリガルヒ集団が何世紀にもわたって地球を支配してきたかを理解する鍵である。オリガルヒたちは私設銀行を通じて資金をプールし、その巨額の富を活用して金融や商業の大部分を支配している。彼らは汚職を得意とし、自分たちに協力する者には賄賂を送り、拒否する者は潰す。彼らはほとんどの国の中央銀行を運営し、貨幣の価格と供給の両方をコントロールし、自分たちの卑劣な目的のために政府の権力を簒奪している。彼らは市場を操作し、できる限りあらゆるところで我々の価格を吊り上げ、そして一般的に、衝動としても戦術としても、嘘をつき、ごまかし、盗む。

この無法な帝国の暴徒を打ち負かす方法は、国民国家の力を利用することだ。捕食現象としての帝国は、基本的に弱肉強食のジャングルの法則に従って動いている。人間を獣化し、衝動と感覚の奴隷にすることで生き延びている。基本的には、臣民があまりにも愚かで自己中心的であるため、帝国の支配に効果的に抵抗できないようにすることで生き延びているのだ。(聞き覚えがあるだろうか?)

デリバティブ市場で間違った賭けをしたために生じた損失に直面したとき、銀行にはどのような選択肢があるのだろうか?いくつかの選択肢がある:新しい資本を得るために株式を発行し、自己資本/自己資本比率に関する規制法の範囲内に収めるために融資を減らす。倒産する。あるいは、預金者の金を盗む。この預金者の資金の窃盗は、ベイルインという新しい「用語」を得た。

銀行救済 - デリバティブの大暴落で、あなたの貯蓄は帳消しになるかもしれない

2012年から2013年にかけて、サイラスの銀行システムが破綻した。 そのわずか4年前、欧州中央銀行(ECB)はEU各国政府の協力を得て、欧州の銀行システムを救済した。2012年までに、EU委員会とEU政府はこれ以上銀行を救済できる状況にはなかった。そこで、新しいタイプの「救済」が開始された。過去の「ベイルアウト」ではなく、「ベイルイン」である。この新しい政策の最初の犠牲者がイタリアで発生した。

2015年11月末、イタリアの年金受給者が銀行の「救済」スキームで16万ドルの貯蓄全額を没収され、首を吊って自殺した。彼は50年来の顧客であり、銀行発行の債券に投資していた銀行を非難する遺書を残した。この救済は、2008年の金融危機の際に大不評だった銀行救済とは異なり、「ベイルイン」(債券保有者が損失を被ること)であり、EUの一般納税者に数千億ユーロの負担を強いるものだった。

次の銀行危機では、破綻銀行の預金者が資金を没収され、株式になってしまう可能性は十分にある。いったん銀行に預けられたお金は、法的には銀行の所有物となる。預けた現金は、銀行の無担保債務となる。銀行はあなたにお金を返す義務があるのだ。もしあなたが大手銀行のひとつに預けている場合、その銀行は「オフバランス」(銀行の貸借対照表に計上されていない負債を意味する)で何兆ドルものデリバティブを保有しているため、その負債はあなたの預金よりも法的に優位な立場にあり、あなたが現金を手にする前に返済されてしまう。

ベイルイン政策は2016年1月1日にEU全域で施行され、米国でも同様に認可された。ベイルインは、2008年のリーマン・ショックと同じような金融危機が二度と起こらないようにするための方法として、国民に売り込まれてきた。量的緩和やその他の超インフレ政策によって政府の資金で破綻銀行を救済する代わりに、預金者や一部の投資家が破綻銀行を救済しなければならない。これは2013年にキプロスの銀行が破綻した際に行われた。

ある人の救済は別の人の救済である。 そして救済される金融商品はデリバティブである。つまり、ポール(ウォール街とロンドン・シティ)に支払うためにピーター(あなたやあなたの家族)を奪うという計画だ。ベイルイン債とは、銀行が債務超過に陥ったときに即座に収奪される債券のことで、言い換えればネズミの毒だ。そんな破綻確実の金融商品をいったい誰が買うというのか?実際、1月に欧州の銀行が債券を市場に流通させることはなかった!

暴落の始まり

中央銀行はこれ以上金利を下げることができず、中国の景気減速もあって、多くのエコノミストは世界的な金融メルトダウンの始まりではないかと懸念している。

また、1月1日に大英帝国の救済政策がヨーロッパ全土で発動されたことで、債券市場は凍りつき、銀行間融資さえも停止していることが早くも指摘されている。実際、1月最初の10日間で、パニックに陥った預金者は欧州の銀行から約400億ユーロを引き出した。

大西洋を越えた金融クラッシュは本格化しており、この崩壊はますます勢いを増している。 米国ではすでに4つのヘッジファンドが破綻した。5兆ドル規模のデリバティブ・バブルに巻き込まれたからだ。同様に、商業用不動産市場のバブルは2007年よりもさらに拡大している。兆ドルにものぼる負債とデリバティブのエクスポージャーに直面したウォール街とロンドンには、次の2つのカードしかない。さらなる通貨増刷と預金者の資金の窃盗、そして投資家の債券と株主の収奪である。これは犯罪的としか言いようがない。この暴落が拡大すればするほど、多くの人命が犠牲になる。現在実施されているこの新しいベイルイン政策のもとでは、あなたやあなたの家族が持っているかもしれないすべてのもの、貯蓄、年金、食料、医療、仕事、家、すべてが、投機バブルを生み出した犯罪的な金融システムを守るという名目で差し押さえられることになる。破綻した世界金融システムを支えるために、貯蓄と雇用が大量に犠牲になるのだ。

問題の根本は、人々が「お金は実際の富である」という嘘に騙され、その嘘の上に金融システム全体が構築されてしまったことにある。 しかし、お金は自明の価値を持つものではない。価値は、人類の生活条件をより良くするための、人類の創造力にかかっている。このシステムが崩壊しつつある今、他の国々は資本規制を導入することで、この事態から自らを守ろうとするかもしれない。ドルに同類はいない。しかし、ドルが支えるシステムは崩壊しつつある。ウォール街やロンドン・シティの銀行家たちのパニックは、水面下で進行している。金融市場が暴落すれば、必然的に戦争が起こる。中東情勢を注視すべき理由がさらに増えた。競合する国々がこの地域のエネルギー資源を奪おうとする中、第三次世界大戦を引き起こす火種が必要なだけなのだ!

実際のところ、第3次世界大戦はすでに始まっている。実際の開戦日は2008年8月で、アメリカがグルジアをロシア攻撃に駆り立てた。ロシアは1週間足らずでこの動きを打ち破った。第3次世界大戦は1つの大きな戦争ではなく、ユーラシア大陸の周辺部での一連の戦争である。

これは第1部の終わりである。物語は第2部「氷の9つのシナリオ」に続く。